It’s the must-have accessory for every self-respecting 21st-century oligarch, and a good many mere multimillionaires: a second – and sometimes a third or even a fourth – passport.

Israel, which helped Russian billionaire Roman Abramovich out of a spot of bother this week by granting him citizenship after delays in renewing his expired UK visa, offers free nationality to any Jewish person wishing to move there.

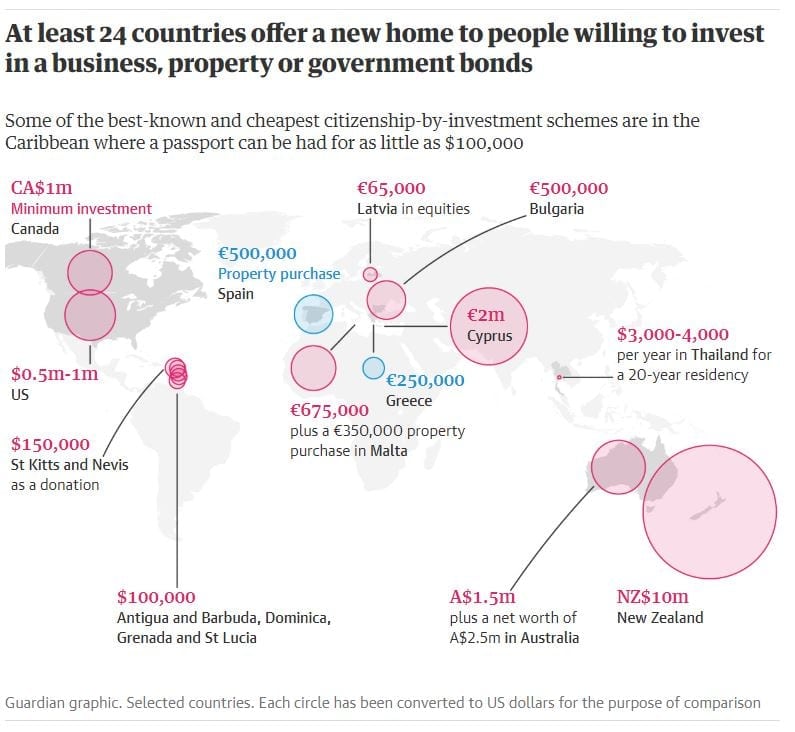

But there are as many as two dozen other countries, including several in the EU, where someone with the financial resources of the Chelsea football club owner could acquire a new nationality for a price: the global market in citizenship-by-investment programmes – or CIPs as they are commonly known – is booming.

The schemes’ specifics – and costs, ranging from as little as $100,000 (£74,900) to as much as €2.5m (£2.19m) – may vary, but not the principle: in essence, wealthy people invest money in property or businesses, buy government bonds or simply donate cash directly, in exchange for citizenship and a passport.

Some do not offer citizenship for sale outright, but run schemes usually known as “golden visas” that reward investors with residence permits that can eventually lead – typically after a period of five years – to citizenship.

The programmes are not new, but are growing exponentially, driven by wealthy private investors from emerging market economies including China, Russia, India, Vietnam, Mexico and Brazil, as well as the Middle East and more recently Turkey.

The first launched in 1984, a year after young, cash-strapped St Kitts and Nevis won independence from the UK. Slow to take off, it accelerated fast after 2009 when passport-holders from the Caribbean island nation were granted visa-free travel to the 26-nation Schengen zone.

For poorer countries, such schemes can be a boon, lifting them out of debt and even becoming their biggest export: the International Monetary Fund reckons St Kitts and Nevis earned 14% of its GDP from its CIP in 2014, and other estimates put the figure as high as 30% of state revenue.

Wealthier countries such as Canada, the UK and New Zealand have also seen the potential of CIPs (the US EB-5 programme is worth about $4bn a year to the economy) but sell their schemes more around the attractions of a stable economy and safe investment environment than on freedom of movement.

Experts from the many companies, such as Henley and Partners, CS Global and Apex, now specialising in CIPs and advertising their services online and in inflight magazines, say that unlike Abramovich, relatively few of their clients buy citizenship in order to move immediately to the country concerned.

For most, the acquisition represents an insurance policy: with nationalism, protectionism, isolationism and fears of financial instability on the rise around the world, the state of the industry serves as an effective barometer of global political and economic uncertainty.

But CIPs are not without their critics. Malta, for example, has come under sustained fire from Brussels and other EU capitals for its programme, run by Henley and Partners, which according to the IMF saw more than 800 wealthy individuals gain citizenship in the three years following its launch in 2014.

Critics said the scheme was undermining the concept of EU citizenship, posing potential major security risks, and providing a possible route for wealthy individuals – for example from Russia – with opaque income streams to dodge sanctions in their own countries.

Several other CIPs have come under investigation for fraud, while equality campaigners increasingly argue the moral case that it is simply wrong to grant automatic citizenship to ultra-high net worth individuals when the less privileged must wait their turn – and, in many cases, be rejected.

The Caribbean

The best-known – and cheapest – CIP schemes are in the Caribbean, where the warm climate, low investment requirements and undemanding residency obligations have long proved popular.

Five countries currently offer CIPs, often giving visa-free travel to the EU, and have recently cut their prices to attract investors as they seek funds to help them rebuild after last year’s hurricanes.

In St Kitts and Nevis a passport can now be had for a $150,000 donation to the hurricane relief fund, while Antigua, Barbuda and Granada have cut their fees to $100,000, the same level as St Lucia and Dominica.

Europe

Almost half of the EU’s member states offer some kind of investment residency or citizenship programme leading to a highly prized EU passport, which typically allows visa-free travel to between 150 and 170 countries.

Malta’s citizenship-for-sale scheme requires a €675,000 donation to the national development fund and a €350,000 property purchase. In Cyprus the cost is a €2m investment in real estate, stocks, government bonds or Cypriot businesses (although the number of new passports is to be capped at 700 a year following criticism).

In Bulgaria, €500,000 gets you residency, and about €1m over two years plus a year’s residency gets you fast-track citizenship.

Investors can get residency rights leading longer term to citizenship – usually after five years, and subject to passing relevant language and other tests – for €65,000 in Latvia (equities), €250,000 in Greece (property), €350,000 or €500,000 (property or a small business investment fund) or €500,000 in Spain (property, and you have to wait 10 years to apply for citizenship).

Rest of the world

Thailand offers several “elite residency” packages costing $3,000-$4,000 a year for up to 20 years residency, some including health checkups, spa treatments and VIP handling from government agencies.

The EB-5 US visa, particularly popular with Chinese investors, costs between €500,000 and $1m depending on the type of investment and gives green card residency that can eventually lead to a passport.

Canada closed its CA$800,000 (£460,000) federal investment immigration programme in 2014 but now has a similar residency scheme, costing just over CA$1m, for “innovative start-ups”, as well as regional schemes in, for example, Quebec.

Australia requires an investment of AU$1.5m (£850,000) and a net worth of AU$2.5m for residency that could, eventually, lead to citizenship, and New Zealand – popular with Silicon Valley types – an investment of up to NZ$10m (£5.2m).

–

You can follow Albert on Gab.ai and Minds or Twitter and Facebook.

Or join the free mailing list (top right) and feel free to comment on story below