If the Loch Ness Monster doesn’t exist, how come there have been so many pictures and sightings? And is Nessie really Nellie?

The first documented sighting of a monster inhabiting Loch Ness was by Saint Columba in AD565. According to this, the Christian missionary was travelling through the Highlands when he came across a group of Picts holding a funeral by the loch.

They explained that they were burying a fellow tribesman who had been out on the loch in his boat when he had been attacked by a monster. Columba immediately ordered young Lugne Mocumin, one of his own followers, to swim across the loch to retrieve the dead man’s boat.

Detecting lunch was on its way again, the great beast reared up out of the water, at which Columba held up his cross and roared: ‘Thou shalt go no further, nor touch the man; go back with all speed!’

And with that, the terrified monster apparently turned tail and ‘fled more quickly than if it had been pulled back with ropes, though it had just got so near to Lugne, as he swam, that there was not more than the length of a spear-staff between the man and the beast’.

The group of Picts, very impressed by all this, converted to Christianity on the spot. However, as evidence of a monster living in the loch for the last 1,500 years, this account seems about as reliable as the story of the tooth fairy.

Not least because St Columba also claimed, a tad implausibly, to have had various other successful run-ins with Scottish monsters, once even slaying a wild boar just with his voice. Nevertheless, many were convinced by the Loch Ness tale.

Then there was silence on the monster front until some strange sightings were reported in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

But the Loch Ness Monster, as we have come to know and love it, it wasn’t really ‘born’ until much later – not until 1933, in fact, when (prosaically enough) the A82 trunk road had finally been completed along the western shore of Loch Ness, connecting the western town of Fort William with the busy port of Inverness on the North Sea.

Providing easy access for tourists and industry alike, the road also offered a route past the picturesque loch for the first time.

Nearby Inverness had a long-standing and hugely popular tradition of hosting an annual circus.

In 1933 Bertram Mills took his circus to Inverness along the new A82 for the first time, where his road crew would have stopped along the banks of Loch Ness to rest and feed the animals. Coincidentally that was when the sightings of the Loch Ness Monster began.

Bertram Mills, ever the entrepreneur, quickly used the local story to his advantage by offering the £20,000 (nearly £2 million pounds today) to anybody who could prove that they had seen the great beast.

It was a sum Mills seemed suspiciously unable to afford to pay out. But the public flocked to the area nevertheless, sightings soared and more people than ever before attended his shows in case the monster might make an appearance.

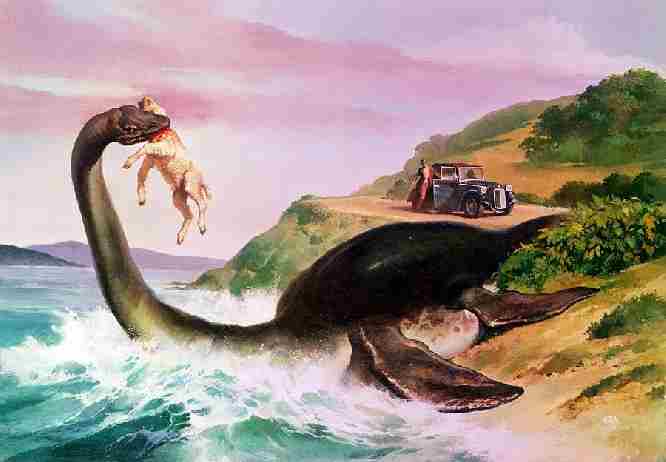

But how could Mills have been so sure nobody could legitimately claim the reward? My theory is that he must have seen the famous photo of a plesiosaur-like creature taken in 1933 near Invermoriston by a Scottish surgeon and had known that it was no monster.

At the time, sceptics claimed the photograph was a fake: the creature it showed must be an otter or maybe vegetation floating on the surface of the loch. It was even said to be an elaborate hoax created using a toy submarine.

But Bertram Mills had seen an elephant swim before and must have realized the photograph taken was most likely of one of his animals bathing in the loch. Although the financial benefits of staying silent about this were obvious.

Soon afterwards, on 14 April 1933, a Mr and Mrs Mackay claimed that they had seen a ‘large … whale-like beast’ idling in the loch and which had then dived under, causing ‘a great disturbance’ in the water. They had immediately reported the sighting to local gamekeeper Alex Campbell.

Campbell, conveniently enough, also turned out to be an amateur reporter for the Inverness Courier. His embellished account of the sighting, entitled ‘Strange Spectacle on Loch Ness’, appeared on 2 May 1933 and brought him instant fame.

The world’s monster hunters, not to mention the media, then descended on an remote area of the Scottish Highlands, only previously known for its fishing.

The dial of Loch Ness Monster excitement was then cranked up even further by the Daily Mail, when they sent in a professional team of monster hunters headed by the wonderfully named big-game hunter Marmaduke Weatherall.

The Mail ran a daily piece on his efforts to lure the monster from its lair and to bag the beast. And within just two days, the headlines announced he had found unusual footprints on the shoreline.

A cast was sent to the BritishMuseum for identification and the Scots were revelling in the global attention their country was receiving.

But the following week they were hanging their heads in shame when the cast proved to be the imprint of a stuffed hippopotamus foot, probably an umbrella stand from some local hostelry or tavern.

Weatherall denied any mischief making and it was never proven whether it had been hunter or hoaxer who had laid the false tracks.

The two most compelling photographs of the ‘monster’ are world famous. One depicts a creature with a long greyish neck that tapers into an eerie thin head rising out of the water, followed by two humps.

Roy Chapman Andrews, an American explorer and director of the American Museum of Natural History upon whom Indiana Jones was based, went on record in 1935 arguing that he had seen the original picture and that it had been ‘retouched’ by newspaper artists before being published.

He firmly states the original picture is of the dorsal fin of a killer whale.

Most other experts disagree. As do I: to my mind, it is clearly the trunk of an elephant, with the first hump being the head and the second its back, almost certainly one of Bertram Mills’s, taken as the circus elephants swam in the loch. Hugh Gray was the photographer;

‘I immediately got my camera ready and snapped the object which was then two to three feet above the surface of the water. I did not see any head, for what I took to be the front parts were under the water, but there was considerable movement from what seemed to be the tail.’

This photograph has been declared genuine by photographic experts and shows no signs of tampering, unlike so many of the others. And that is because, in my view, it is a genuine photograph – of a genuine elephant. No retouching required.

But the best-known photograph is the one taken by surgeon Robert Kenneth Wilson on 19 April 1934.

Indeed it must be one of the most instantly recognizable pictures ever taken.

From a distance of two hundred yards what has come to be known as the ‘Surgeon’s Photograph’ shows a grey ‘trunk’ of around four feet protruding from the water with a hump directly behind it and clear disturbance in the water around.

Once developed and declared genuine, the picture was bought and published by the Daily Mail and the Loch Ness Monster industry was properly born.

Curiously enough, when asked what he thought he had seen, Wilson claimed to have been too busy setting up his camera to take proper note, but thought there was certainly something strange in the loch.

The next question then should have been: ‘Why didn’t you wait around for a while to see if it returned?’ because then he may well have seen the elephant surfacing, as it would have had to sooner or later.

Then again, perhaps he did, but greed rather than valour influenced the better part of his discretion.

As recently as March 2006, Neil Clark, curator of palaeontology at the Hunterian Museum in Glasgow, has stated (thus confirming something I have believed for many years):

‘It is quite possible that people not used to seeing a swimming elephant – the vast bulk of the animal is submerged, with only a thick trunk and a couple of humps visible – thought they saw a monster.’

Dr Clark also notes that most sightings came around the time of Bertram Mills’ reward offer for evidence of the monster. He himself believes that most other the sightings could probably be explained away by floating logs or unusual waves.

More Mysterious World with Albert Jack

But just as it seemed the eminent professor was about to finally blow the Loch Ness Monster out of the water, so to speak, he was asked by the BBC whether he believed there was a large creature living in the loch. To which he responded: ‘I believe there is something alive in Loch Ness.’

And he’s not wrong, is he? There must be ‘something’ alive in the loch; in fact there are lots of living things swimming around in it. But at least he didn’t go on to say it was a 1,500-year-old sea monster, which it would have to be, as that is the premise upon which this whole story has been constructed.

But to be fair to Dr Clark, the Loch Ness Monster is big business for Scotland. Consultants have estimated it to be worth in the region of £50 million per annum and rising.

More that 500,000 tourists travel to the area every year in the hope of sighting the beast, despite Bertram Mills’ reward expiring with him.

Some claim the industry has even created 2,500 new jobs. And the Monster Spotting Tour comes in at £15 a head. Dr Clark would not be popular in his home country if he finally dispelled the myth many love and even more rely upon.

Since the elephant-heavy 1930s there have been dozens of sightings of objects of varying shapes and sizes. Even if paddling pachyderms are no longer the likeliest explanation, other theories are possible.

Loch Ness is actually a sea lake, fed from the Moray Firth in the North Sea via the River Ness. Furthermore, the Moray Firth is one of the areas of British seawater most frequented by porpoises, dolphins and whales.

Indeed seals and dolphins have been filmed in the loch many times. If the mind wants to see a monster, three partly submerged dolphins swimming in a row could easily provide the illusion of a thirty-foot, three-humped creature in the gathering gloom – especially after a few drams of the local malt.

I have myself encountered a few three-humped monsters after a lively evening out before now.

The BBC has used sonar and satellite imagery to scan every inch of the loch and found ‘no trace of any large animal living there’.

But, as it has always been the case with myths, legends and fables, while it is possible to prove the positive by producing irrefutable evidence, it is never possible to prove the opposite argument.

We could dam Loch Ness and drain it. We would then be able to take everybody still perpetuating the myth down into this vast new dry valley and show them every nook, cave and rock cluster, but still the hardcore believers would reply:

‘Ah, but Nessie may well be out in the North Sea at the moment just limbering up for another appearance.’

But of course that is not the reason at all. Everyone from Columba (who told that miraculous story, embroidered or otherwise, which led to his canonization) onwards has profited from retelling the tall tale of Loch Ness.

The only surprise is that so many people have, and still do, strongly believe there is an unidentified prehistoric monster living in a Scottish loch. Some argue that is a historical fact; I know it’s just a hysterical one.

I’m here to inform you, kids – there is no such thing as the Loch Ness Monster. Just don’t tell anyone it was me who told you. – Albert Jack

Albert Jack AUDIOBOOKS available for download here

Albert Jack’s Mysterious World