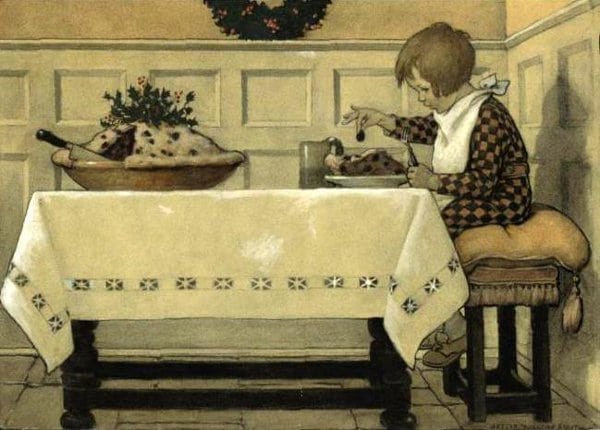

Little Jack Horner

Sat in a corner

Eating a Christmas pie;

He put in his thumb

And pulled out a plum

And said, ‘What a good boy am I!’

Before the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1536 there were more than eight hundred religious foundations in England with over 16,000 monks and nuns.

During the following five years, they were all seized by the Crown and their land and buildings were either sold off or gifted to supporters of the king.

One of the last to go was the ancient Benedictine abbey of Glastonbury and the tale of its own dissolution is said to supply the origin of this rhyme.

The Abbot of Glastonbury at the time was Richard Whyting, a rich and powerful figure who had been a signatory to the First Act of Supremacy (1534) granting King Henry VIII the legal authority as head of the Church of England.

This was an outright rejection of the power of Catholicism and allowed the king to divorce and marry again.

Despite choosing the king over the Pope, a basic requirement for keeping one’s head in sixteenth-century England, Whyting resisted the dissolution of Glastonbury Abbey for as long as possible.

It wasn’t just that it was one of the wealthiest in the kingdom, it was also a place of huge religious significance.

The abbey was allegedly founded by Jesus’s Joseph of Arimathea – the man who donated his tomb for the burial of Christ’s body after the Crucifixion – to house the Holy Grail.

Joseph is said to have arrived by boat over the flooded Somerset Levels; disembarking at Glastonbury Tor, he stuck his staff into the ground, which flowered miraculously into the Holy Thorn (legend has it that the tree still bursts into bloom every year on Christmas Day).

The colourful story was widely believed, Elizabeth I using it as evidence that Christianity in England pre-dated the introduction of Roman Catholicism, thus legitimizing her role as Defender of the Faith.

Whyting chose to placate, some might say bribe, the king. He sent his steward, Thomas Horner, to Hampton Court with the deeds to twelve manor houses, concealed beneath the crust of a large pie, posing as a gift.

In those days, during property transactions, it was not uncommon for the deeds to be hidden or concealed in transit to ensure they would not fall into the wrong hands, as the actual holder of the deeds was deemed the rightful owner.

On the way, legend has it, Thomas Horner delved into the pie and pulled out the deed for a plum piece of real estate, Mells Manor House in the village of Mells, Somerset.

And that, apparently, is all he needed to do to become the new lord of that manor.

But the bribe failed and in January 1539 Henry’s chief minister, Thomas Cromwell, sent his royal commissioners to Glastonbury to see for themselves what was actually going on down in darkest Somerset.

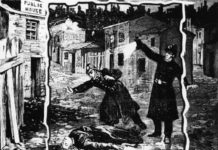

As a result of what they found, Whyting was sent to the Tower of London so that Cromwell could question the Abbot in person, and from there he was returned to Glastonbury on 14 November 1539.

The following day he was tried for treason, with Thomas Horner as one of the jurors, and found guilty within only a few hours.

That afternoon, Richard Whyting and two of his senior monks, Roger James and John Thorne, were dragged by horses to the top of Glastonbury Tor, where they were hanged, drawn and quartered.

Abbot Whyting’s head was then displayed above the gates of the deserted abbey as a reminder to others to obey the king without question. Meanwhile Thomas Horner was presumably busy making his removal arrangements.

Unsurprisingly, the descendants of Thomas Horner, who still live at Mells Manor, dismiss the legend as ‘pure fantasy made up by the Victorians’.

Jack’s honesty, it is claimed, is supported by John Leland’s Itinerary (1540–46), a study of ancient buildings and monuments presented to Henry in 1549 that states: ‘Mr. Horner hath boute [bought] the lordship of the King.’

An alternative account suggests that the king gifted the manor to Horner and that the original title deed, bearing the royal seal, survives in the family’s possession to this day.

Note: During the 1500s, the slang term for £1,000 was ‘plum’, just as in modern terms a ‘score’ is £20 and a ‘monkey’ £500. Back in the sixteenth century, £1,000 was a seriously large sum of money, as well as being the fixed amount some politicians received for taking on certain government roles.

This was considered by the average person as a vast sum of money for doing very little, and that is why these posts became known as ‘plum jobs’ or ‘plum roles’.

The expression ‘plum’ has been used ever since to describe anything of great value that is usually gifted rather than earned. – Albert Jack

Albert Jack AUDIOBOOKS available for download here

Pop Goes the Weasel – Nursery Rhyme History